As a user experience (UX) researcher, you gather insights on a user’s online behavior patterns, constantly striving for balance in design for customers and business needs accordingly. Think of it as a train, once it’s built, the engineers have completed the major task of getting it to do its job. UX researchers, here, are like inspectors and detectives who constantly monitor it, how it is performing, on the lookout scanning for potential threats, if anything needs the attention of maintenance personnel, and what the primary stakeholder — the customers, think about their experience with it. Then, providing appropriate recommendations to dedicated teams.

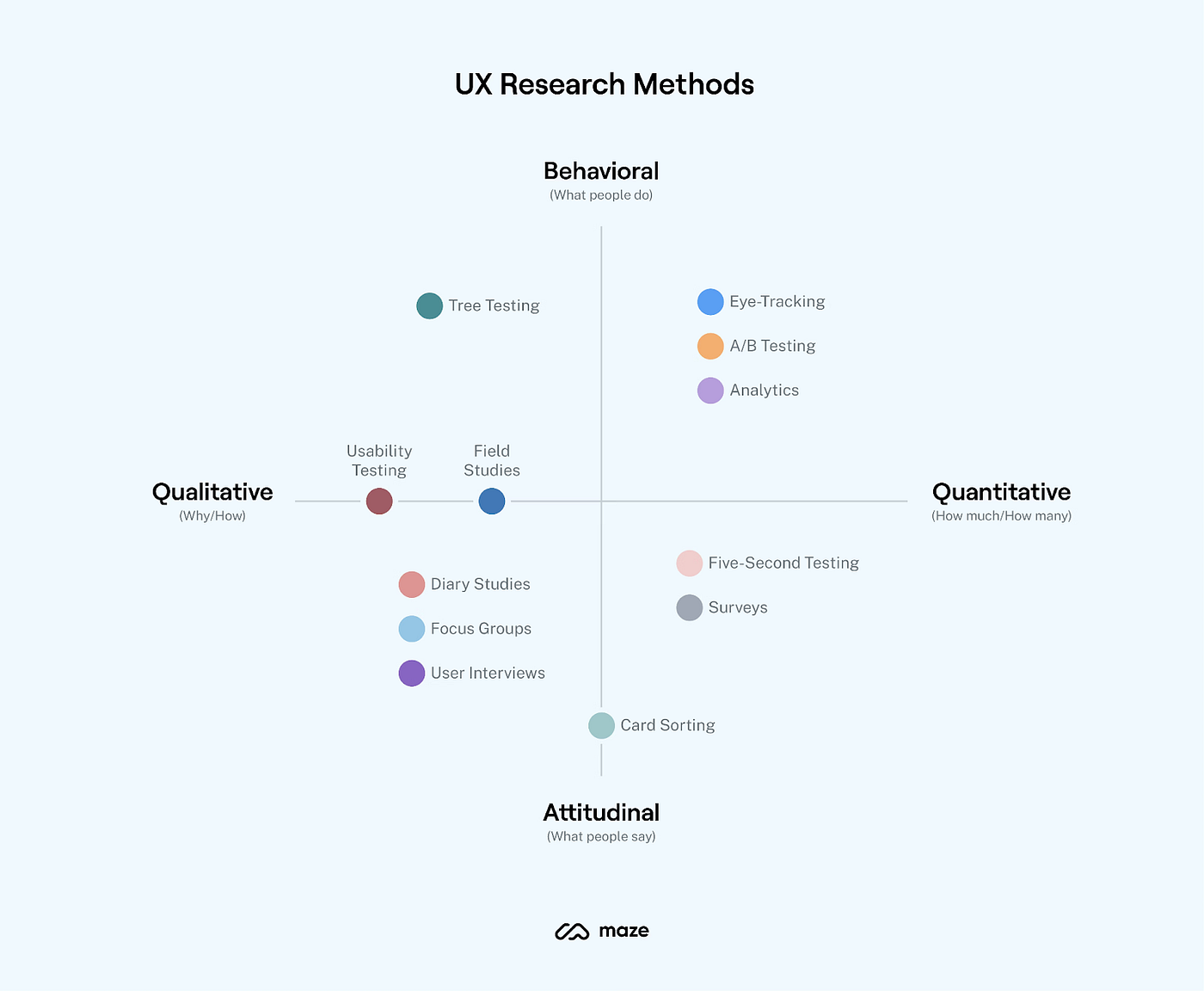

In order to form unbiased, factual, and accurate recommendations, UX research is conducted within 4 overall research categories: qualitative, quantitative, attitudinal, and behavioral.

Qualitative asks the questions — Why? How?

Quantitative asks the question — How much? How many?

Attitudinal asks the question — What people say?

Behavioral asks the question — What people do?

These categories are then broken down with different methodologies that can be used to reach conclusive findings, some of these include:

It is very important to know why you are conducting research and how its results impact business decisions. This not only allows you to plan ahead, but also lets you know which processes to take, what questions to ask, but most important — who to ask those questions to? Sometimes, narrowing down on these questions, you will also realize that primary research is not necessary if user data can be derived with the help of analytics teams.

I like to consider myself as a sort of ‘corporate nurse’ where I get to listen to user’s concerns and understand their potential pain points. It then allows me to come up with solutions on how their online experience with using QIC products can be improved.

A large part of my job consists of both, primary and secondary researches where I am responsible for:

A lot of times, it is easy to get prone to our own assumptions which can distance us from what we think is better and what users might find beneficial. These assumptions may not always translate into real-life use cases. A number of things can impact this:

One of the key reasons why assumptions can form are our own individual biases. Biases exist everywhere in every aspect of our daily life. Human beings are built to recognize patterns and come up with solutions based on past experiences. It is not to say having a bias is a wrong thing. However, when we are conducting research, it is important to list down what possible biases we might have and how they will impact our interpretations.

A research project starts by defining its purpose, how it will be conducted, who it will include, where it will take place, and how the findings will be implemented. This, of course, is a standard practice for me when approaching a primary research as opposed to secondary. One document template I’ve found very useful is the Google UX Research Template. If you are someone who plans to conduct UX research, I highly recommend abiding by it.

Some of the steps I take in the primary research process include:

A very important and comprehensive (see what I did there) UX research I conducted was for the used car market in Qatar. The objective of this research was to find all the steps a buyer and a seller must take in order to meet their desired outcomes. This, obviously, starts out with the plan. The questions I had to ask myself in order to create this research plan went something like this:

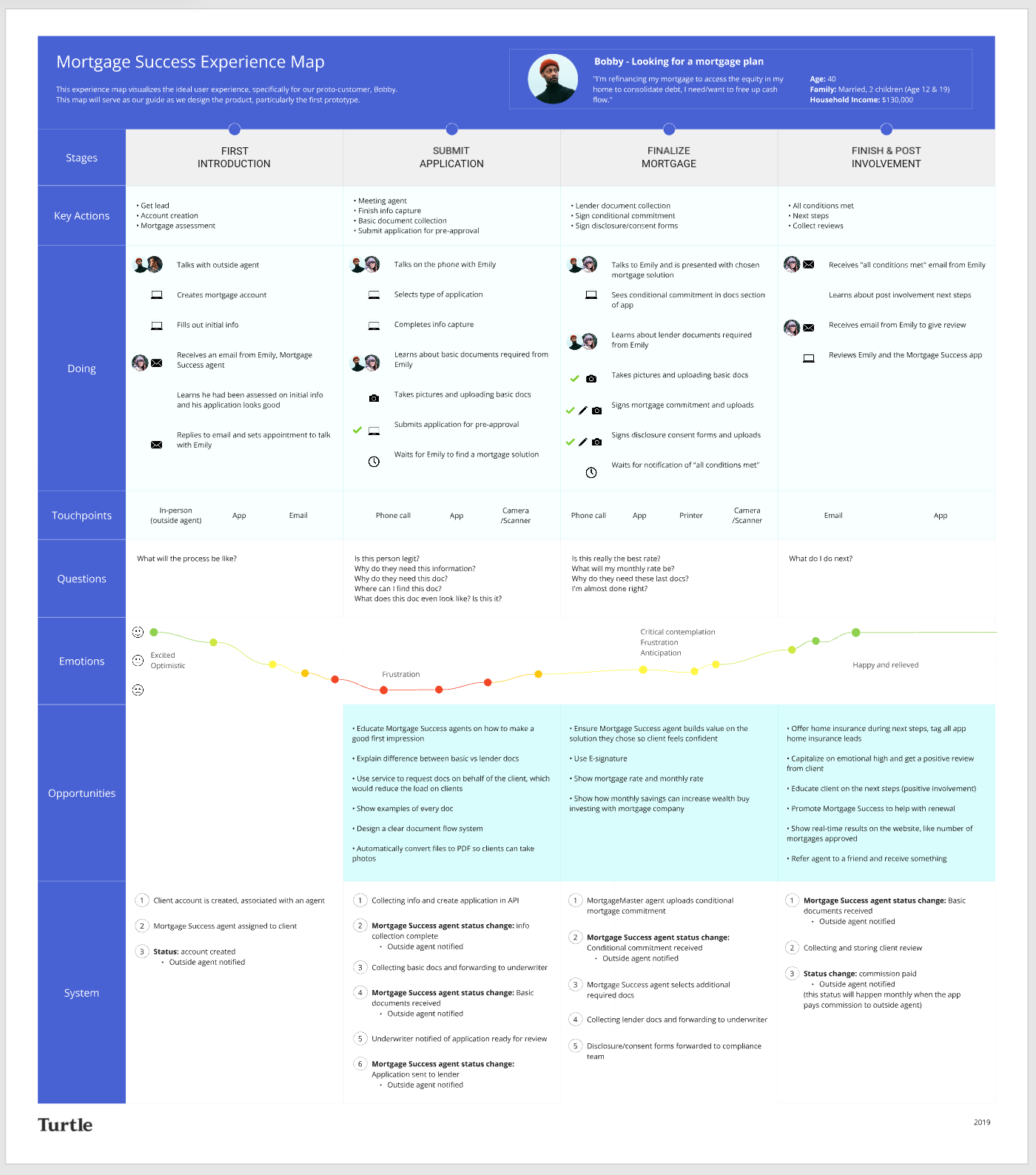

My approach when conducting a research like this starts by building a skeleton first. What do I mean by this? Imagine the research plan is DNA in the human body, once we know what needs to be done, we can identify how to build it. For me, it goes something like — skeleton, internal organs, flesh and skin. Once I have filled out as many details in the research plan, I create the ‘skeleton’ which is how the insights will be presented. In this case, it was going to be presented to the design team, therefore, I went for a very visual approach. Next came in the ‘internal organs’ which meant filling in all the details from the user interviews that I had done. Lastly was to add the ‘flesh and skin’ which just meant sculpting the information to limited key points instead of every ‘mechanism’ inside being visible (below is a sample template by Turtle).

Continuing from the last example, recruiting is one of the main challenges I face in my role. The average conversion rate for interviews ends up being 1–2% from batches of 500 people that I send a participant request for at a time. This is contributed to many things including, but not limited to:

All of these are valid reasons for why users are hesitant to partake in these researches. It is important to remember that product and research are relatively new fields in this part of this part of the world. People are not very exposed to the idea of how their feedback impacts the industries around them. Which is fair because sometimes processes and resolutions can take weeks, if not months to get implemented and people, without seeing instant change, assume no one listens to their feedback. Then why bother giving it in the first place?

Moving forward, it has become my priority to make sure that we are able to incentivise our research projects because people’s time is valuable and a simple ‘thank you’ can sometimes not be enough reason to give someone 20–30 mins of your time.

It is important to remember that you will make mistakes, they are inevitable, but being able to adapt and rectify course is where your strength should lie in these cases. The most common mistakes people tend to make when researching, including myself, are because:

Now, it is important to note you can never be 100% accurate in your findings, but you can get close to 99.99%. That is the goal of each research. I highly advise asking questions to the relevant teams and its stakeholders, clarifying the purpose of why they want a research done, and keeping them in the loop at all times throughout the process. Lastly, I would advise to be unapologetically curious and not fall into the trap of what you already believe to take at face value and perceive it to be true. That’s advice I would honestly give for someone to apply in their day to day life as well.

At QIC, that is what I am making sure that we are able to do to the best of our ability. I absolutely love this role, I enjoy everything it entails, but most importantly, it allows me to gather insights on online users behavior. A very relevant field to the way we engage everyday with the world around us.